In the world of poetry, every word holds significance, transforming mundane language into profound expressions of human emotions and experiences. Within this intricate tapestry of language, the title of a poem occupies a pivotal role—it is the window through which readers engage with the poet’s vision. Yet, a common query arises: are poetry titles italicized? The answer, while seemingly straightforward, leads us into a deeper exploration of the conventions of poetry, the intricacies of written language, and the significance of literary presentation.

Understanding the treatment of poetry titles requires delving into the specifics of various style guides and the traditions surrounding poetic works. Different styles impart distinctive rules that govern how titles should be presented, and these distinctions can significantly affect the way poetry is perceived by audiences.

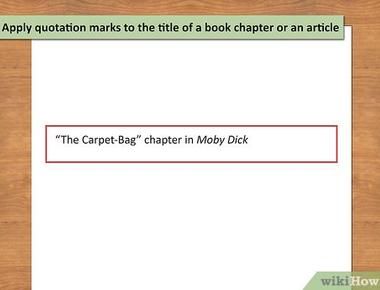

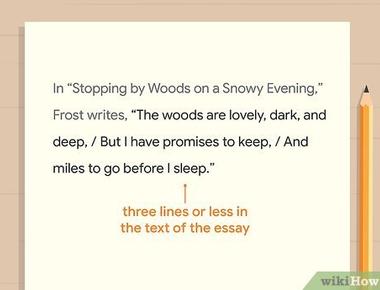

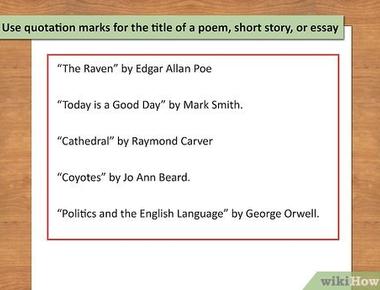

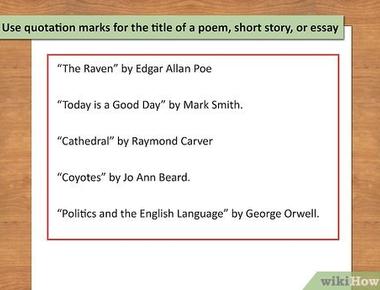

Traditionally, many style guides advise that the titles of longer works, such as books or collections of poetry, should indeed be italicized. This provides a visual cue, marking the title as a significant entity within the written text, thus elevating the work’s stature in the eyes of readers. Conversely, shorter works—like individual poems, articles, or songs—are typically enclosed in quotation marks. This delineation between the longer and shorter titles establishes a balance, guiding readers through the literary landscape.

Consider a collection of contemporary verses, where the overarching title might be italicized: The Collected Poems of Emily Dickinson. Each poem within that collection, however, would be presented with its title in quotation marks: “Because I could not stop for Death.” This visual differentiation leads to a refined understanding of what constitutes the core of a poetic piece versus the backdrop of a larger collection.

The italicization of larger works emphasizes an anthology’s cohesive narrative, inviting readers to appreciate the broad canvas crafted by the poet. It suggests a deliberate intent by the author to convey a series of interconnected sentiments, themes, or styles. In this way, the format is not merely bureaucratic; rather, it is an articulation of literary hierarchy, where the individual pieces are revered yet contextualized within the greater artistic endeavor.

However, the conventions of formatting titles are not homogenous across all styles. The Modern Language Association (MLA), American Psychological Association (APA), and Chicago Manual of Style each have standards that writers and academics should consult to ensure fidelity to their communication’s framework. For instance, MLA specifically recommends italicizing the titles of full-length books and collections but retaining quotation marks for shorter works. Conversely, APA guidelines align closely with MLA, but they emphasize clarity and simplicity in presentation, often favoring straightforwardly styled titles.

These varying rules prompt intriguing questions about artistic choice and the evolution of literary formats. In modern digital communication, poets and writers occasionally eschew traditional formatting altogether, opting instead for stylistic individuality that resonates with their voice. This innovation challenges the reader to engage with the text on a different level, transcending conventional understanding of titles and formats.

Moreover, this divergence in title presentation can also resonate with thematic elements within the poetry itself. A poem emphasizing transient moments or ephemeral emotions might be represented without traditional capitalization or formatting, evoking a sense of urgency or spontaneity. Such decisions underscore the poet’s voice and can enhance the reader’s immersion into the poetic experience.

When considering poetry written in free verse or experimental forms, the rules of traditional formatting may seem archaic. Poets like E.E. Cummings forged new paths, creating a disjunction between text and expected norms. Observing how poem titles are presented can reflect broader artistic intentions, inviting readers to grapple with their interpretations of both content and form. Thus, the decisions regarding italics or quotation marks frequently lay a nuanced canvas upon which a poet paints their message.

In addition to the artistic considerations, understanding the purpose of titles is essential. A title serves as the first point of engagement for readers—drawing in attention, sparking interest, or even signaling a thematic exploration. For instance, take the poignant title “The Road Not Taken” by Robert Frost. Its significance reverberates through the subsequent lines, prompting contemplation, introspection, and connection. Here, the title’s visual presentation, ideally italicized or quoted based on its context, enhances its impact.

Ultimately, the question of whether poetry titles should be italicized leads us to profound considerations of not only a title’s visual presentation but also its conceptual significance. As literary conventions evolve, so too do the methodologies by which poetry is crafted, presented, and interpreted. Writers and poets will continue to navigate these waters, balancing tradition with innovation.

In conclusion, the italicization of poetry titles is much more than a mere stylistic choice; it reflects the essence of literary appreciation itself. Whether writers adhere to established conventions or venture into more experimental territories, the treatment of titles will invariably impact the reader’s experience. The next time you delve into a poem, pay attention—not only to the words but also to how its title frames your understanding. In that very moment, the interplay of format and meaning takes on a profound significance, ensuring that poetry remains a dynamic form of expression that resonates through the ages.

Share

Related Posts

Quick Links

Legal Stuff